From Heritage to Horizon.

Ten Years. Ten Stages.

One R&D Philosophy.

When we took over the business, we felt a profound sense of responsibility — and deep respect — for the moulds and the four decades of accumulated intelligence they represented. Only a fool would undermine forty years of craft: the trial and error, the hard-won construction knowledge, the quiet formulas that delivered World Championship titles, Olympic medals, and multiple world-fastest times.

Those moulds — and the laminate recipes that shaped every boat emerging from them — were not just tooling instructions. They were a legacy.

Our objective was never to erase that past, but to understand it — and then carry it forward through focused, deliberate research and development. We chose to build on what had already proven itself, while methodically expanding what was possible.

This chapter offers insight into the intent and structure of that R&D cycle — a cycle that, after ten years, has now reached completion. Everything we set out to achieve in our first decade has been delivered.

Some stages refined capability.

Others unlocked new choice.

Together, they form a single philosophy: respect the heritage — and design for the horizon.

Ten years is a long enough horizon to stop chasing proof — and start explaining principles.

Stage One: New Carbon moulds

Heritage Is a Responsibility, Not a Museum

When we acquired the business, the moulds were effectively the core assets that came with it. Our objective was not simply to preserve them, but to truly understand why those shapes had delivered national and international success — including world-fastest times — and whether there were areas where we could responsibly contribute to their evolution.

Heritage only matters if it continues to earn its place.

At the time of handover, the active fleet consisted of:

5 single hulls

4 pair/double hulls

4 four/quad hulls

2 eight hulls

We still retain access to most heritage moulds for integrity repairs where required. But from the outset, it was clear that preservation alone would not be enough. Some limitations were immediately visible. Others would only reveal themselves over time.

So we made a deliberate early decision:

Respect the past — then take it forward.

That meant changing not just shapes, but methods:

Full 3D scanning of existing hulls

Engagement of a marine engineer to review performance and apply targeted refinements

Transition from hand-sanding and hand-shaping to CNC machining

→ not for speed, but for repeatable accuracyMoving from fibreglass moulds to carbon fibre moulds

→ to eliminate thermal movement in the oven and prevent shape creep over time

→ delivering stability, longevity, and consistency

This stage was not about reinventing the wheel. It was about discipline — and treating its roundness as a practice, not a destination. Small, uncompromising improvements, applied consistently, compound into reliability.

This way of working aligns closely with kaizen: progress that is incremental, quiet, and relentless.

Stage Two: Saltwater Slide sYSTEM

Performance Meets Reality

The objective here was to solve a real problem created by the unforgiving saltwater environment.

Corrosion does not care about intention, pedigree, or reputation. Anyone operating near the coast understands this intimately.

The Saltwater Slide became our first truly original, system-level development. The brief was deliberately simple: create a long-term solution to a problem that had long been accepted as inevitable.

This stage marked a turning point in our thinking.

It was here that we discovered something important — the quiet satisfaction of solving a significant real-world problem with an elegantly simple idea.

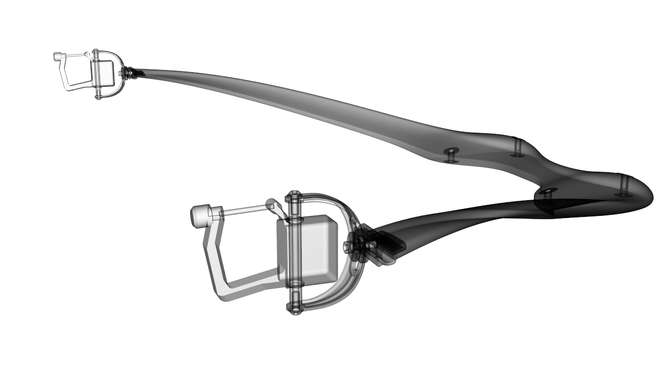

STAGE THREE: CARBON RIGGING

Meeting Market Expectation by Building Capability

Carbon rigging was never a speculative ambition.

It was a clear market expectation.

Internationally, elite programmes had already normalised carbon riggers across all boat classes. In New Zealand, the expectation existed — but the capability did not.

There is a reason many companies can build boats, while only a handful globally can consistently design and manufacture elite-level carbon riggers. This is where structural engineering truly lives.

Closing that gap required more than copying shapes or chasing marginal weight reduction. It demanded the development of engineering capability from the ground up: structural design, analysis, tooling, and repeatable manufacture.

This stage marked a clear shift — from building what was possible to building what was required.

The objective was not just simply a lighter and stiffer rigger.

It was proof of capability: the ability to design, build, and refine carbon rigging systems across sculling and sweep — from singles through to eights.

The market moved.

We moved with it.

SINGLE CARBON RIGGERS

Developed in collaboration with Emirates Team New Zealand, the single carbon rigger marked a turning point.

Not just lighter — but structurally smarter.

This was the foundation. The point at which theory met repeatable execution. The deeper story of this development will be explored in a dedicated episode.

STAGE FOUR: COASTAL ROWING

R&D did not stop at flatwater racing shells.

Coastal boats forced a different way of thinking — about impact loads, safety margins, and long-term use. Those lessons didn’t stay at the coast. They fed directly back into everything we built afterward, strengthening our approach across the entire range.

Stage Five: Sculling Carbon Rigger Range: Doubles and Quads

What we learned through the single rigger could not remain isolated.

The same principles needed to be applied to larger boats — not by scaling blindly, but by re-validating loads, stiffness, and geometry under entirely different demands. This stage was about carrying capability forward, not repeating effort.

Stage Six - Pair Carbon Rigger

The pair presented the highest-elevation challenge in the sweep range.

Once solved, it unlocked the structural logic and geometry required for larger sweep boats. This stage quietly enabled everything that followed.

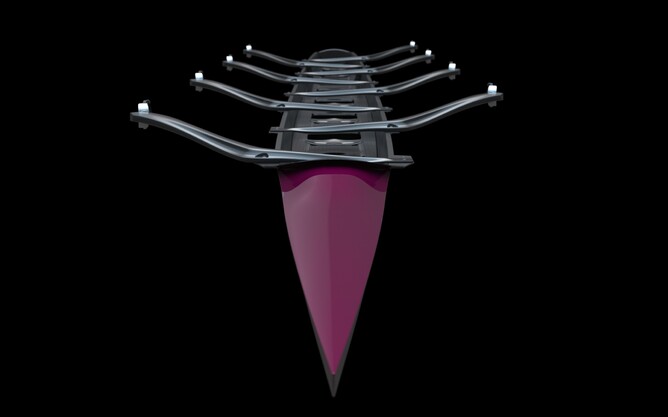

Stage Seven - Sweep Carbon Rigger Range: Four and Eights

As with the sculling range, development grew from the inside out. Each larger class demanded its own validation — similar thinking under different constraints.

This work wasn’t about novelty, but about extension: carrying the same capability across classes and proving that the system held under increasing complexity. Where stages may appear similar, that repetition is deliberate.

In other words, when the thinking stayed the same, the challenge changed. Meeting those challenges — one class, one configuration, one geometry at a time — was as significant as any visible breakthrough.

The engineering challenges behind carbon rigging sit at a different level of complexity and deserve a conversation of their own.

Stage Eight - Signature Deck Design — Singles

This was the first visible step toward a unified Laszlo design language. A quiet indicator of where our thinking was heading, and how future developments would begin to speak the same visual and functional language.

STAGE NINE: New Eight Hull: Savage

Unlocking a New Performance Window in The Goldilocks Zone

For many years, school rowing in New Zealand relied on two highly successful eight hull shapes:

L17.2 — flatter, stable, widely favoured by girls’ programmes

L17.5 — faster, more aggressive, popular among boys’ and men’s crews

Both shapes earned their place.

Both delivered results.

Both continue to perform strongly today.

But over time, something else became clear.

Between these two proven options sat a performance window that had never been deliberately explored — not because it was ignored, but because the tools required to target it precisely did not yet exist.

It was an opportunity.

Savage was developed to focus on that space intentionally.

The design brief was precise:

Retain the speed characteristics of more aggressive V-shapes

Introduce subtle stability markers to support confidence and consistency

Create a performance environment where crews can thrive without compromise

The performance target remained uncompromising. Savage was conceived as a true weapon — Olympic-level speed, optimised for the 70–85 kg average crew range.

Paired with bow-mounted carbon riggers, crews experience the same setup, balance, and speed behaviour found in high-performance international environments — whether competing at junior level or beyond.

The advantage is not novelty.

It is familiarity.

And familiarity reduces adaptation cost.

Reduced adaptation cost often shows up as speed.

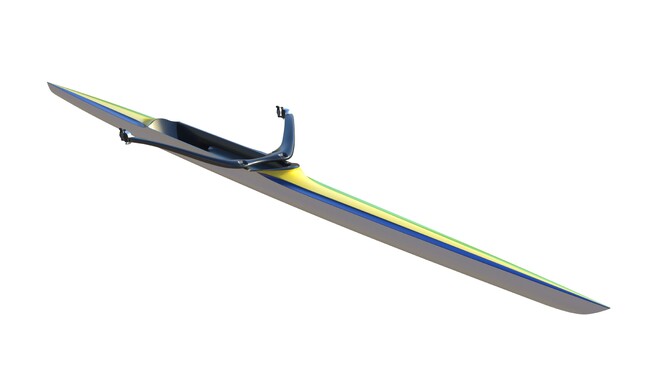

Stage Ten: Carbon HydroFin

Currently in real-world testing.

By Stage Ten the direction was clear. Demand for advanced, hydrodynamically shaped fins had become a market expectation. The market wanted carbon before the infrastructure to support it existed. To meet that demand, we zoomed in on the critical aspects of fin development and set out to create a complete system:

A carbon fin for increased stability

A hydrodynamic profile to reduce drag

A fin box compatible with both aluminium and carbon fins

Seamless integration with existing aluminium T-bars, allowing older boats to be retrofitted cost-effectively

Crucially, the system needed to be fully interchangeable — enabling crews to train on aluminium fins, race on carbon, and carry out the change themselves without specialist installation.

This is the present tense of our R&D journey — the point where the next cycle begins to take shape.

OUR r&d PHILOSPHY

If we had to summarise our approach, it would be this:

Build technology that didn’t previously exist in New Zealand —

and make it accessible across the entire rowing community. From the smallest schools to super clubs.Leave room for happy little Eureka! moments along the way.

Every stage outlined here exists because someone asked a question, raised a concern, or challenged an assumption.

Manufacturing in New Zealand is not easy. Distance, scale, logistics, and cost are real constraints. Which is why we’re proud — not just of what’s been built, but of how it’s been built.

With respect to the Elders (see what we did there?) who came before us — KIRS and Krutzmans — we were excited to take the baton.

We’re incredibly proud of what our small — albeit ambitious — operation has accomplished by consistently punching above its weight. And yet, it feels like the real journey is only just beginning. We’re only now settling onto the start line.

Signing out to go back to the drawing board — and probably the CNC —

We’re here for rigging and grinning — The Laszloz